Recognize Persian Rugs by Region from Design & Pattern

Design & Pattern: The Simplest Way to Recognize Persian Rugs by Region Each region in Iran known for rug weaving produces carpets with unique characteristics. Among

Iranian designs worldwide are primarily famous by the name of their place of origin, such as Isfahan, Kashan, Mashhad, and Sarouq within the country. As a result of the movement of carpet weavers and patterns, these designs have become less known by the name of their place of origin.

Iranian handwoven carpets require a new scientific and artistic classification. According to this classification, specific differentiations must be made concerning:

This categorization provides a structured framework for a more comprehensive understanding of Iranian handwoven carpets, considering various factors contributing to their diversity and unique characteristics.

In essence, the name of a handwoven piece, if it’s valuable, should reflect its cultural coherence. It should summarize the traditions, style, and place of origin of the handwoven item, making the social context in which it was crafted evident. Additionally, by specifying the birthplace of each type of weaving, if the handwoven piece is significant, its cultural identity will become apparent.

Defining the location and especially the historical context of the weaving will help determine the cultural domain to which it belongs within the classification of handwoven items (e.g., carpets, kilims, rugs).

Ancient Art and Islamic Structure Patterns:

All patterns inspired by the decorations and designs of ancient buildings, structures, and Islamic architecture belong to this category. Although handwoven designers have made minor alterations to the original patterns in some cases, the fundamental structure and similarity to the original building designs have been preserved.

This classification is an old method used by many carpet, kilim, and rug designers and experts.

Some researchers have introduced specific modifications to this classification, while others have categorized these patterns into two main sections and eight primary groups. The two sections include patterns exclusively inspired by nature and patterns named based on the role, appearance, place of design, construction, tribal names, ethnicities, individuals, ancestral influences, and historical or religious significance.

In her valuable book titled “Handwoven Carpets of Iran,” Cicely Edwards discusses:

“Are the patterns and motifs of Iranian carpets each indicative of a philosophy or a way of life? Iranian designers aim to create delight through the alignment and beauty of their patterns. They have either drawn inspiration from real life (nature) or utilized external sources. In both cases, caution should be exercised when associating these shapes and motifs with Sufi and mystical thoughts. Perhaps these motifs are simplified representations of animals, plants, and birds that have evolved. What is certain is that when a weaver sits behind her loom, she contemplates more than she sees.”

The structure is the overall framework of a design, displaying its dominant image and surroundings.

Form refers to the internal relationships between elements within a composition. As the most significant indicator, the line is crucial in creating a record in the pattern. Line characteristics such as line width, direction, extension, curvature, intersecting angles, and the space between lines are all considered linear indicators.

The content of all handwoven textiles (carpets, rugs, and kilims) features the use of various plant and animal motifs, including:

Plant motifs:

Such as trees, Afshan (a specific plant), Gol-dani (Vase design used in prayer rugs and mihrabs), buteh (a bushy plant), lachak Toranj (a plant motif), Moaharamat (prohibited motifs), Golestan (a garden motif), baagh (a garden motif), paaliz (a rug motif), Behesht (paradise motif).

Animal motifs, such as Animal hunting and chase scenes.

Images or delicate patterns used, including eight-petaled and twelve-petaled flowers, bird motifs, the peacock, mountain goat, sheep, horse, fish, birds, and more.

(Hunting ground Rug)

One could argue that Iranian art is symbolic and emphasizes the function of symbols in various artistic fields in Iran. This characteristic strengthens the connection between Iranian art and mythology and mythical concepts. Each symbol exhibits three prominent qualities: derived from nature, conventional, and replicable.

Mythology shares practical characteristics with symbolism and, along with other sociocultural elements such as religion and belief systems, becomes part of individuals’ lifestyles after humans regain intelligent life.

In this regard, ancient Greek concepts like “Agathos” (goodness), “Chresimon” (usefulness), “Tekhne” (Artistry), “ٍros” (love), “Mimetis” (imitation), “eternity,” (Immortality) and “kalon” (beauty) are invoked in the mythological thinking that embodies the unity of the spirit and the body, where the body is an emblem in the form of a mythical symbol, representing internal thoughts of individuals.

In the course of art history, during the Renaissance, we witnessed the entry of rational art and intellectual activity (liberal art) into the field of cultural activities. Following this perspective, practical art (technical art) also entered the arena. However, throughout its historical journey, Iranian art has always been rooted in rationality, founded on insight, intelligence, and the creative minds of its artisans.

Aristotle analyzed the components of a work of art in three dimensions: knowledge, action, and artistic creation. These ascending stages have become embodied simultaneously in the minds of Iranian artists. An example of this is the circular symbol that embodies celestial bodies, existence, mythical culture, and philosophy. This symbol is also interpreted as representing philosophy and intellect. In principle, angular and static movements symbolize masculinity and psychological thinking from cultural perspectives.

In examining weight and rhythm, the structural pattern of handwoven textiles (carpets, rugs, and kilims) mostly features swirling or, in other words, the symbol of life and existence. It not only conveys psychological meanings but also indicates femininity, bringing us closer to the reality that female weavers and designers have played a significant role in our country.

This consistency (harmony) between form and content, which links the external form to the mythical thought content, is the same form of connection that Hegel mentions when he refers to the harmony of subject and concept and, in general, cultural attitudes in different eras have a direct relationship with creating people’s mythical beliefs.

Although each era encompasses specific conceptual content from a cultural classification standpoint, these precedents do not apply when creating mythology. For example, we may encounter a mythological character who, in terms of cultural classification, is associated with prehistoric magic beliefs.

In classifying cultural periods, we first come to a time when all cultural attitudes of the people were related to magical beliefs. We find these beliefs particularly in the minds of humans in prehistoric times. After the invention of writing or, in other words, humanity entering historical times, we go back to the pre-mythological era. After that, we encounter mythological beliefs in a later age, where there is a transition from anthropomorphism to human beliefs in God and God to humans. In another period, these cultural beliefs gave way to metaphysical beliefs, a time when gods ascended from Earth to the heavens. Subsequently, religious beliefs replace these cultural beliefs in humans, leading us to the modern cultural era, where forms and shapes have entirely disintegrated, and the subject has lost its significance.

“The role of handwoven textiles (carpets, kilims, and rugs) and mythology, by the classification applied to Iranian carpet designs, is such that the most mythical forms are predominantly found among these plant and animal motifs, as well as architectural and composite patterns.

To explicitly state that the depiction and portrayal of these forms on the carpet precisely align with the interpretation of concepts now explored by the greatest mythologists, sociologists, and historians is an undeniable fact. However, these are the linguistic expressions of people who have experienced the power of conveying such thoughts in the valley of designs and colors in wool.

Humans share common spaces of thought. This makes it seem like we have heard a passage in a book or its narration in someone’s tone as if it had been a constant presence in our minds, perfectly harmonizing with our intellectual horizon. Thus, among various cultures, the heavens, the Earth, trees, and water consistently reappear with shared meanings, colors, and harmony, aligning with each other in application.

Just as in the mythological time of (illo in tempore) Paradise, the mountain tree, columns, or evergreen plants connect the Earth to the heavens to enable human ascent.

In primordial times, encountering deities happened. Accordingly, the stature and significance of animals in the eyes of early humans are very high. Animals know the secrets of life and nature, even the mysteries of longevity and impermanence. Friendship with animals and understanding their language is considered a symbol of wisdom.

These constructive myths are also reflected in the perspective of individual carpet weavers. The tales of Paradise, descent, human impermanence, the mystery of death, and the discovery of the soul—all these themes are manifest in the work of the carpet weaver (carpet, kilim, rug), enhancing the weaver’s imaginative abilities and creativity.

These people delve deeper into the art of life, revealing the sensory and spiritual capacities in their existence beyond time. This is a form of mental exercise aimed at transcending time, a form of symbolism where all myths related to bird-human (or winged beings) are included, signifying a kind of ascension towards the sky.

The subject of flight, escaping the confines of earthly existence, and freedom from human conditions is one of the oldest themes in folklore, with global distribution. Beyond the passage of time, becoming weightless and free from human constraints, the transformation of the human body into a spiritual entity.

The Noble Eightfold Path of Buddha’s ascent, the Seven Degrees of Mithraism and Sevenfold Ascension in Shamanic Rites’ represented in Iranian carpets around the periphery of the central field, are structurally the same as the symbolic motifs in India, Central Asia, and the Middle East.

The concept behind it is the escape from the world to the transcendent passage through the seven heavens and reaching the apex of the cosmos, which is also seen in Sami traditions, emphasizing the centrality of cosmic symbolism in Iranian carpets.

Form, design, and color rush to the aid of meaning and visually convey it to the beholders as the adornments of eternity, granting power. This central position returns to the primordial era—when there was still no pollution, disrespect, weariness, and colorlessness.

Thus, we see Buddha kneeling on a blue lotus instead of stepping on the Earth. The ascent of the soul is always accompanied by a kind of serenity and the attainment of purity, for it is the shaper of the dynamic unity of our senses.

This matter is somewhat akin to the exercise of the soul towards leaving time. It turns to symbolism, where all myths related to bird-human (or winged beings) find their place and signify ascending toward the sky.

The subject of flight, the pursuit of perfection, and the pursuit of escape from the material world have always been integral to human perception.”

Jung associates with the collective unconscious of humanity and believes that the slightest connection with this collective unconscious results in the experience of eternity for humans.

The flower vase patterns, Afshan (Overall flower design)

These patterns are linked to the myth of the creation of existence. The flower vase, which has a comprehensive connection to Mother Earth and the goddess of fertility, carries a similar meaning and is seen in various forms in the design of Iranian carpets.

The birth of humanity from the Earth is a universal belief. This profound sense of emerging from the Earth and being born from it, like the inexhaustible fertility of the land and bestowing life on elements such as trees, flowers, grass, and rivers. “Fertile Earth” is where life begins and serves as a great witness to the enigma of instructing a new form of existence.

The concept of Mother Earth and its manifestations in various patterns is rooted in the history of religions, dating back to the Stone Age. Sometimes, Earth becomes the goddess of death. Death is likened to a seed planted in the bosom of the Earth to give life to a new plant.

Earth is the source of inexhaustible creation, and in all religions, death is a transient passage to another form of existence. It is part of the renewal cycle and the beginning of a new life.

This way of thinking and perspective is reflected in artistic works in various forms and through multiple tools. It is an awakening interpretation that suggests that the end of the world is never absolute, and there is always a quest for a new creation, another form of renewal.

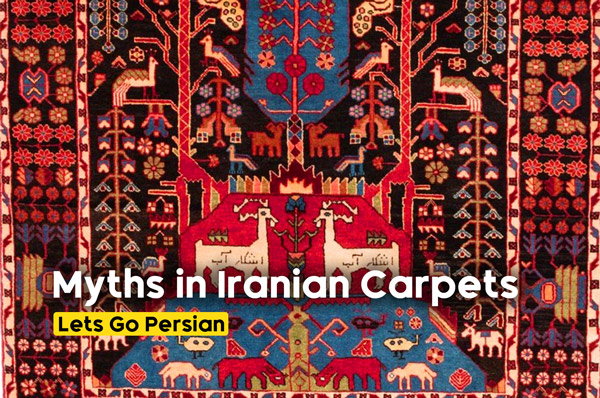

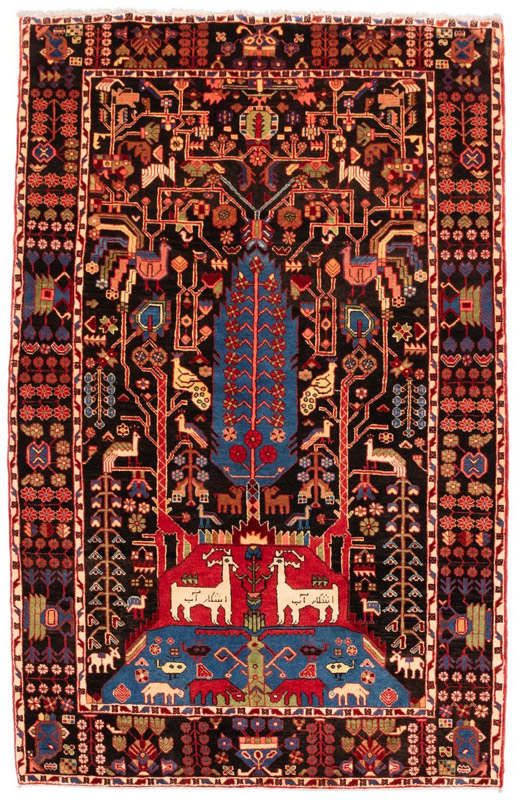

Tree Motif

The tree motif is one of the most common patterns in Iranian handwoven textiles (carpets, kilims, and rugs). It is used in various forms as the primary motif or as part of the pattern and texture.

This motif is among the essential mythological symbols that have been incorporated into the works of great mythologists. Mircea Eliade, for instance, states:

“The symbolization of the world tree is equivalent to symbolizing the entire universe. The realm of this tree is in our unconscious and deeper life. Employing this symbol unites mental activity and the mind. In myths and religions, this symbol represents renewal, infinity, cyclical rebirth, life’s source, youth’s fountain, and reality.”

(Nahavand Carpet)

Such a myth is an expression of truth because it conveys sacred history and thus becomes repeatable. The tree motif, which is often designed as a cypress tree, is used in various tree patterns, including Gol-o-Bolbol (flower and nightingale), Vase, Muharramat (forbidden designs), Garden or Paradise practices, and Palis (a type of tree pattern), in various textures, such as Qab-Qabi and Kheshti-Butti.

In addition to carpets, the cypress tree motif is widely used in fabric weaving techniques such as Termeh and Ghalamkari (Calico Work) and Ghalamzani (Etching) on metals and stones, as well as in various traditional Iranian arts. This widespread use and long-term credibility have transformed its shape, resulting in more than 60 forms of this motif today.

Regarding the cypress tree depicted as a Plant, there are multiple interpretations: it can symbolize the mystical flames of Zoroastrian fire altars, resemble the shape of an almond or pear, depict an adaptation of the Indian plant, which also found its way to Iran from there, or perhaps the most beautiful and closest description is that it represents the curved and windblown form of the cypress bush in nature.

The transformation and evolution of the cypress into a Plant can be separated into three periods in pre- and post-Islamic art. Initially, the cypress was a sacred and religious symbol, signifying beauty, eternal spring, and masculinity.

In this phase, the cypress tree is depicted in its natural form in the civilizations of Assyria, Elam, and the Achaemenid art without decorative characteristics. The portrayal of the tree in this period is somewhat limited, and the vertical cut of the tree is represented with horizontal branches, which requires utmost precision and finesse in sculptures like the Persepolis reliefs.

Continuing from the first period, the cypress motif in the art of the Parthian and Sassanid era is no longer a sacred tree, although its significance remains. However, this significance no longer carries secret or religious connotations but represents a traditional motif’s continuation.

In the second phase of the cypress tree’s evolution, concurrent with the influence of Islamic civilization, the cypress departs from its ancient roots. It transforms into ornamental depictions, distancing itself from its religious nature. Although evidence suggests that the belief persisted until the twelfth century that the cypress was the symbol of eternal beauty, it is from this point that it is depicted as a bush and becomes closer to an ornamental motif.

(Bakhtiari Carpet)

From this point on, the cypress is depicted as a simple paisley pattern and becomes closer to an ornamental motif. From the sixth century onwards, the cypress bush and the embellished cypress branch emerged from the simple forms, and the paisley pattern took on a more complete and final form.

The emergence of the cypress bush in Iranian handwoven textiles occurs when symbols are not merely reflections of shared needs and beliefs but also possess aesthetic and decorative aspects. In addition to the Tree of Life motif, mention can be made of the Afshan motif.

Furthermore, among these motifs is the three-branched flower bush or three flowers, where the central flower is taller than the two other flowers on the same level. These motifs symbolize the rising of the sun, its zenith, and its setting.

The two pairs of guarding birds, pomegranate flowers, eight feathers, and more all represent in some way the idea of the infinite, eternity, and the unbroken chain of existence within these plants and trees.

Medallion design (Lachak Toranj) – Corner Pattern:

The mythical story of the Garden of Eden is once again manifested distinctively in Iranian textiles (carpets, kilims, and rugs), appearing as a central water basin within the carpet’s design, known as “Torenj.”

(Torenj Carpet)

This basin, adorned with animal and plant motifs inside or around it, symbolizes the space of paradise and symbolizes its blessings.

The continued use of this pattern in the dynamic and creative minds of artisans has led, over time, to changes, either partial or complete, by the elements of the design and its aesthetic representation. It has been deduced that restricting the design’s space to a single “Torenj” has gradually led to the division of a single “Torenj” into two halves and eventually into four quarters, with each quarter taking its place in the corners or small compartments of the design.

The initial pattern of this design concept is believed to have been derived from the “Golshan” pattern, symbolizing paradise. Religious life and its connection to the realm of conscience play a vital role in providing individuals with spiritual goodness and happiness, urging them to avoid evil deeds. The concept of striving for excellence and being rewarded for actions has been a demand on humans even in ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian religions. The continuity of customs and beliefs filled with mysteries throughout history also suggests that humans adhere more to what satisfies their conscience and heart than to what pleases their intellect.

These concepts of religious life and their relationship with the superior human mind have been with humans throughout the ages, accompanying them in their personal, social, economic, cultural, and artistic lives. Essentially, the role that the religious life of nations plays in the birth and transformation of history often begins with mythological patterns.

Mythology belongs to the world of the human mind and transcends time. Even though time is a material concept, the sanctity of mythological rituals aims to draw humans out of earthly time and into mental time. It is in this transition that individuals become committed.

As long as a person balances between the attractions of material time and mental time, religious life dominates their actions and behavior, whether in mythology or history.

Religious life helps individuals seek refuge from the current and dynamic times, providing them tranquility in stagnant and static times. In passing through this ordeal, with the help of mythology, they find their way to divine history, transcending human history.

Weavers have used the fish-like pattern since the late Timurid period and throughout the Safavid era. Because it was prevalent in Herat during the Timurid period, it is called “Herati.” However, the etymology of the word “fish” and how it became popular in woven textiles (carpets, kilims, and rugs) is unclear.

The Herati pattern has been used in various parts of Iran, and there is a noticeable difference in its design from east to west of Iran. For example, the size of the Herati motifs in the east, especially around Qaen, Torbat-e Jam, and Torbat-e Heydarieh, is more significant than in western and central Iran, such as Kurdistan.

This mythological pattern is not limited to woven textiles (carpets, kilims, and rugs). Still, it can also be seen in coinage, high relief sculpture, painting, architecture, and even on the crown of Tigranes the Great, one of the kings of Armenia.

(Coin of Tigranes II the Great, Antioch mint)

Its foundation and principle consist of two or four curved leaves that enclose a giant flower.

The interpretation of the central flower, sometimes called the blue water lily or Shah Abbasi, varies. It is said that initially, the leaves represented fish, which transformed into leaves during the Islamic period. The central flower may have once symbolized a human face, which also transformed into a floral shape.

In general, this pattern, along with the myth of the tree, cypress, hunting ground, and many other intricate designs used in Iranian woven textiles (carpets, kilims, and rugs), carries symbolic meanings and allusions due to the lasting influence of the Mithraic cult in Iran.

Mithra, or Mehr, was a significant deity in the histories of various countries and eras. His worship extended from the West to England and East to India.

(Swastika or Wheel of Mehr)

Mithra, once worshipped by people thousands of years ago, is still respected by Zoroastrians. He is a god of covenants and guards over agreements, order, and truth, even in agreements between two nations.

He is fiercely hostile towards covenant-breakers or “Mehr-Dorujans,” but he is kinder to his faithful followers. Iranians regard Iran as the land of covenants, and before going to war against countries opposing the Mithraic covenant, Iranian warriors, mounted on their horses, would pray to Mithra, along with the Sun and the eternal sacred fire.

Mithra played a crucial role in religious rituals and Zoroastrianism among Iranians. A remnant of these rituals is the Mehregan festival, celebrated on the 16th day of the Mehr month. Iranians express their gratitude and devotion to the Sun, Mehr, and eternal fire.

The water lily is associated with both water and the Sun. The significance and value of the water lily in the mythology of the Mithraic cult offer much to contemplate.

The water lily holds many beautiful and enigmatic secrets, which Maurice Maeterlinck explores in his book “The Intelligence of Flowers.” This same flower adorns Iranian woven textiles (carpets, kilims, and rugs) with various names and patterns, enriching their decorative tapestry.

Animal Motifs in Persian Carpets

Among the patterns inspired by nature in Persian carpets and textiles, mythological meanings play a significant role. These patterns, whether in the main field of the material or the smaller motifs within it, often incorporate symbolic and metaphorical senses.

Myths have indeed provided an understandable and rational framework for the relationship between humans, other creatures, and the order of the universe in every culture throughout the world. This perspective is rooted in the intellectual interpretations of ancient cultural eras, particularly in rural and tribal communities, which closely resemble the beliefs and customs of traditional Iranian carpet, kilim, and rug weavers.

This is why symbolic elements are prevalent in various roles within these textiles. Allegory conveys meanings beyond their immediate and apparent interpretations, which carry inherent symbolism.

Allegory is multifaceted and polysemous, just as trees, the moon, the sunset, and the sea consistently carry meanings beyond their literal interpretations.

The organizational and structural power of myth allows it to transcend time and place. Sigmund Freud employed myths that originated centuries before his time to delve into the concept of the unconscious.

“Religion and magic are not the only means humans communicate with the mythological world.”

Edward B. Tylor mentioned animism or animatism, the belief that everything has an independent anima or mana, which determines their movement, stillness, presence, or absence. For humans to dominate nature, they must align the anima of objects with their own.

Offerings, needs, and sacrifices are all acts stemming from animism. Magic and totemism have also been added to mythological studies, as scholars like James George Frazer have argued. Frazer believed that culture transitioned from the magical stage to religion and then to the scientific background.

Perhaps one of the closest concepts related to the introduction of animal motifs in Iranian woven textiles (carpets, kilims, and rugs) is the concept of Cassirer. This concept revolves around language, the idea of existence, and the evolution of human consciousness, and myth, in essence, is a language of this intellectual dynamism.

The lion is one of these mythological animal motifs in Iranian woven textiles that lifts the veil on its imagery through mythological narratives. The use of lion motifs in various forms has been prevalent in Iran, especially in Fars, from ancient times.

(Lion Sign Carpet)

This figure is prominently depicted on the reliefs of Persepolis and can be seen on the staircase of the Apadana Palace. Additionally, it can be observed on many Sasanian vessels and textiles. The image of the lion has been used in various contexts, often symbolizing majesty, power, and grandeur associated with kings.

The battle between the lion and the bull may symbolize an ancient myth, possibly related to the struggle of Mithra with a bull, which is present in Mithraic myths. This motif is repeatedly found in the remnants of the Mithraic tradition. It suggests a connection between the lion and the god Mithra and the lion’s association with the bull’s slaying, representing the bestowal of blessings.

In the Mithraic tradition, the lion may represent an earthly form of Mithra and the sun. In later Zoroastrianism, this battle was attributed to Ahriman. The slaying of the bull, which itself symbolizes the blessed moon by the lion, represents an act of bestowing blessings.

The story of Kalileh and Demneh also features the killing of a bull by a lion. In Western Asia, the goddess Ishtar was often depicted riding on a lion, signifying her earthly manifestation.

In many contemporary weavings from Lorestan, you can still see animal motifs with a strong resemblance to the art of our ancestors from 3000 years ago. Among these similarities, the lion motif is quite prevalent.

Furthermore, during the reign of Mohammad Shah Qajar in 1973 AD, the sun (representing Mithra or Mehr) and the lion became the official flag of Iran. This symbolism demonstrates the lion’s connection to Mithra.

(Stone lion – Aligudarz)

With the wisdom of the Iranians, the lion continued to serve new functions even after the Islamic era and became one of the traditional elements of the new religion. Perhaps one of the most commonly used animal motifs in Iranian carpets, kilims, and rugs is the depiction of the lion and the struggle between two animals. Nevertheless, in the text and margins of some of these handwoven carpets, smaller motifs are still used to enhance the beauty of the space, known as minor motifs or illustrations.

These illustrations can include depictions of birds, peacocks, sheep mou, particularly goats, and horses. Dr. Parham has explored these motifs in her study of Fars rugs.

Geometric Patterns

Among the patterns above, which have a long history and mythical significance, not only in Iranian handwoven textiles (carpets, kilims, rugs) but also in other Iranian arts, we can mention the Swastika, stars, chessboard patterns, and Toranj pattern with four or eight armed designs.

The antiquity of most of these patterns is associated with their use in well-known crafts that have endured to this day, especially in pottery that dates back to millennia before Christ.

The Swastika, symbolizing Mithra or the Sun, is extensively used in handwoven textiles, and it’s interesting to note that this symbol is often carved on the wooden doors of rural houses.

The Aryan Swastika symbol can be traced back to ancient civilizations in Iran, China, India, Japan, European prehistoric cultures and Native American tribes. Its origin is in Central Asia, with the oldest known examples found in Iran from the 5th and 4th millennia BC in Susa.

In its initial forms, this pattern was depicted as circular or with four arms and broken. Its use in Persian carpet weaving can be seen as a symbolic reference to the centrality of the Sun in ancient Iranian civilization.

The Eight-Pointed Star has been a representation of the Sun and sunlight in various historical periods. This pattern was used with a simple, single-color depiction of white and black flowers on pazirik (The oldest Persian carpet ).

pazirik (The oldest Persian carpet )

The Eight-Pointed Star, also known as the “Duwazdah Par” or “Doodeh Par,” was present in Iran’s Scythians, Medes, and the 2nd millennium BC cultures.

Let’s consider the Twelve-Pointed Star from the 2nd millennium BC as a symbol of the acceptance of the solar calendar and its twelve months. The Eight-Pointed Star with two colors can represent the four seasons and their distinction from each other, symbolically representing the number four, which has positive connotations.

Chessboard patterns from prehistoric times were symbols of the interplay of water and mountainous regions, mainly found in pottery from Shush, Parsa, and Nahavand.

The Toranj patterns, often mistakenly referred to as “Ratil” (Tarantula), are symbols of the moon, which gradually transformed into a representation of the Sun over time. These patterns have a history dating back five thousand years and have undergone minimal changes, with the four corners representing the symbol of the moon system, which later became associated with the Sun.

Conclusion

The classification of the presented motifs in this context has been based solely on the tangible experience of the images through the study and examination of written sources from esteemed researchers like Dr. Parham and others. The conditions and facilities for the empirical research of many handwoven patterns (carpets, kilims, rugs) woven in various Iranian provinces were unavailable.

It is clear that if the culture of researcher-building in its original home, which is not the cradle of universities, and special facilities are provided for this work and the support of interested researchers, the nests of thousands of cultural and art issues of this country that now need to be explored and explored may open one after the other.

The purpose of this brief exploration was to provide a different perspective on the study of the content of Iranian culture and art. Myths themselves are a reflection of the cultural attitudes of each person.

It is evident that if the mythical echoes of these patterns are still prevalent in Iranian carpets today, this heritage is a testament to the generations that have continued this cultural and artistic tradition. Ancient peoples, even those without written language, possessed such talent and capability that they could reshape their mental qualities.

Their way of life and relationship with nature sometimes led to these mental attitudes. The development of all human abilities cannot co-occur in one epoch.

Despite all cultural and social differences among human groups, the human mind has standard capabilities and can produce everything under specific cultural conditions. It is at this moment that mythology is also born.

Relying on cultural roots, depending on the national mental primordiality that has created the sacredness of the Iranian nation’s culture and art in her work, and in this symbolic representation, all the factors used, if carefully analyzed with contemplation and awareness, have found their place.

(Qashqai tribe weavers)

Using dots, lines, volumes, and colors in Iranian handwoven textiles (carpets, kilims, rugs) has been a skillful selection and combination. The drop is a uniting and generating element desired in four broad areas. When used colorfully in space, it can also be a source of emergence and convey a particular meaning with any color.

Suppose we delve into the comparative study of the colors used in handwoven textiles (carpets, kilims, rugs) from different regions of Iran. In that case, we will find that, in addition to seeing beautiful and skillful principles of color coordination side by side and their best placement in the secluded spaces and front and back borders, we can also find meanings and mythical concepts associated with them.

Indeed, the mythical blue of the desert region is distinct from the blue of the sky in the Kurdistan or Fars regions, and artistry seeks to provide visible visual differences for expressing these distinctions.

At the same time, through comparative study, we may discover the differences and untold similarities among these cases, revealing their hidden truths. All the above examples prove that the art of Iran, especially handwoven textiles (carpets, kilims, rugs), can be profoundly and thoroughly investigated from various cultural, artistic, and social perspectives.

Once unveiled, the mystery, wonder, and beauty of creation will significantly enhance the mental and sensory connections of the audience and the national pride and dignity of Iran far beyond the boundaries of aesthetics and mental affiliations.

Written by: Dr. Nazila Daryaie

References :

Design & Pattern: The Simplest Way to Recognize Persian Rugs by Region Each region in Iran known for rug weaving produces carpets with unique characteristics. Among

Since ancient times, carpet weaving has been practiced throughout Iran, including in cities, villages, and among various nomadic tribes. The term carpet refers to both pile

Wool is one of the most essential and foundational materials in the art of Persian carpet weaving. It is used both in the pile and warp

One of the most iconic motifs in Persian art is the Boteh Jegheh—a timeless design deeply rooted in the traditions, beliefs, and mythology of Iran. It’s

Among the many elements that make Persian carpets uniquely beautiful, the design stands out as one of the most defining. While there are numerous patterns—such as

When it comes to Persian carpets, one of the most critical elements that determines both quality and character is the type of knot used in the

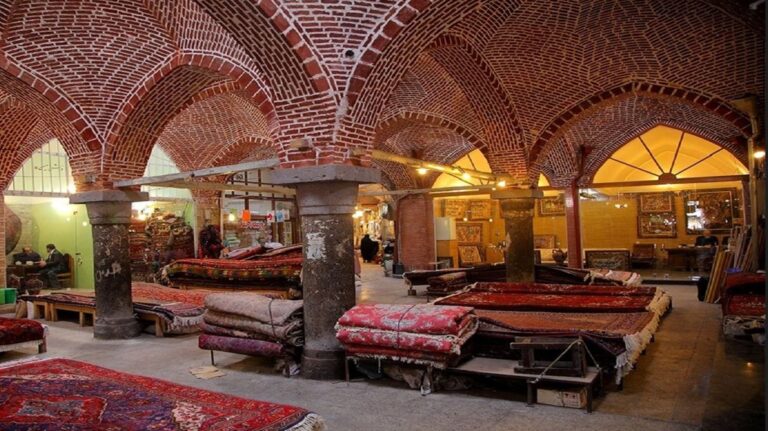

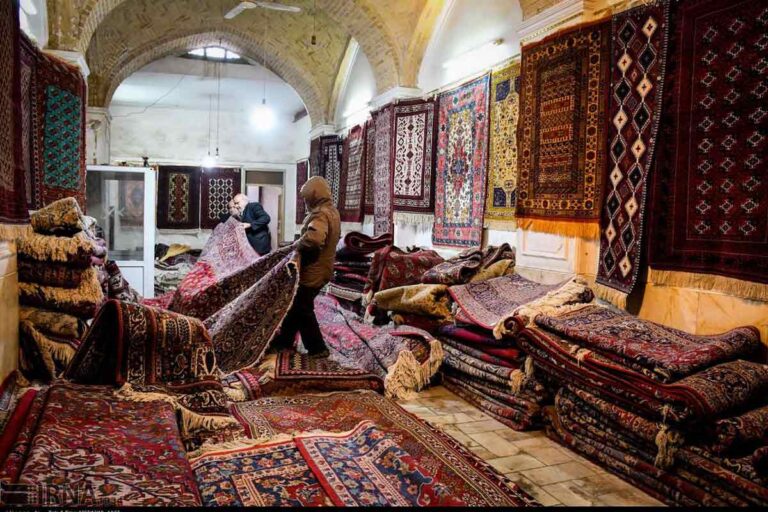

Walk through any carpet bazaar in Iran and you’ll notice something remarkable: two seemingly similar carpets can differ in price by a factor of 100—or more—per

As a family-owned Persian carpet shop, we bridge the gap between passionate collectors and skilled weavers, supporting both the artistry and the heritage of this timeless craft.

We guarantee fair prices for Original Authentic Persian Carpets

Address:

Shop No-GD 04, Dragon Mart 2 –

Dubai – United Arab Emirates

No.36 – 10th st. – Hafez Ave. –

Shiraz , Iran

Block 19 – Kooye Mohandesan –

Kish Island, Iran

Email info@letsgopersian.com

We bring you not just a carpet, but a masterpiece with a story — directly from the hands of Iranian artists to your home.

By working directly with artisans, we help preserve centuries-old traditions while offering our customers a chance to own a unique piece of original cultural heritage.